The ATA Magazine invited Elders from the ATA Indigenous Advisory Circle, which included 11 First Nations, Métis and Inuit Elders and Knowledge Keepers from across the province, to participate in interviews. Three Indigenous Elders among the group gathered for a roundtable discussion (held via Zoom) to discuss three fundamental questions. What ensued was a free-flowing and engaging conversation that spanned an hour and a half. Here are excerpts from that discussion.

Elders

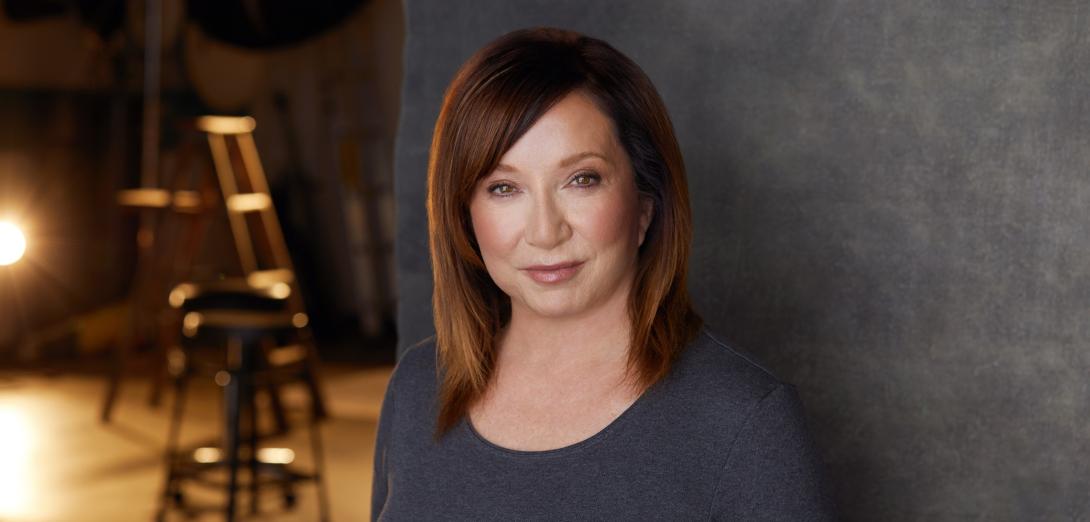

Doreen Bergum

Born in an era when it was illegal to express one’s Métis culture, Doreen Bergum dove into her culture at age 55, when laws changed. She learned music, dances and handicrafts that were secretly shared during her childhood. Currently, Doreen is the Métis Elder for the Homeland of the Métis Nation of Alberta Region #3 and an internationally recognized jigger. She shares her culture with students in schools, colleges and universities and creates storyboards and museum displays.

William Sewepagaham

William Sewepagaham is from the Little Red River Cree Nation in northern Alberta and is fluent in Cree. William earned a bachelor of education from the University of Calgary and a masters of education from the University of British Columbia and spent his career as a director of education, a principal, a classroom teacher, guidance counsellor, as well as in curriculum development. William also worked as a community liaison at various times and is a highly respected Elder across Alberta who was in great demand in schools.

Mary Cardinal Collins

Mary Cardinal Collins is originally from onihcikiskwapiwinihk Saddle Lake First Nation, from the clan Wecokan (wîcôkân “helper” in SRO). Her mother is of Métis heritage, although she was brought up on the reserve in the 1940s. Mary went to Blue Quills Indian Residential School when she was seven, but while other children lost their language, she didn’t.

Facilitator

Melissa Purcell

Tthebatthı Dënésułıné

(Smith’s Landing First Nation), Treaty 8 – Irish

Executive Staff Officer, Indigenous Education, ATA

What advice do you have for teachers on engaging in Indigenous education with students, families and school staff?

Doreen Bergum

When I was growing up, I was taught the seven sacred teachings of love, respect, humility, courage, wisdom, honesty and truth. When I was in school and someone asked me a question about who I was, I was embarrassed because I had never embraced my culture. I think you have to reverse it and make sure students don’t get embarrassed, so they can come out and be proud of who they are, especially of their ancestors, their parents and their culture.

I believe that the biggest thing is respect—respecting youth, respecting the teachers and just building up that encouragement to be proud of who they are.

Or you can consult Elders. They can come in and tell stories and share their culture. We just have to remember that not all Elders are the same, and the teachings and values and all stories are not the same.

William Sewepagaham

It’s very important that we talk about this topic. School is something — some parents think it’s not for them, … and some don’t really want to go there, but if they do, it should be celebrated.

Always acknowledge [parents]. Always smile — a smile goes a long way.

And say, “Hi, how are you? My name is so and so.”

Mary Cardinal Collins

If you get a chance to have personal relationships … I know we talk a lot about relationships in our teachings, and I know when I first started teaching, which was a long time ago, there was a real emphasis on having professional relationships. And by that I think it was meant that it wasn’t really personal — you’re the teacher and there’s a big boundary there. There still is a boundary, but I think for any of these relationships with Indigenous Peoples, it has to be on a personal level.

Indigenous education has to be embedded in all the subject areas and it just needs, I think, to be mentioned on a regular basis that this was an Indigenous way of looking at things.

How can teachers learn about cultural protocol?

Why is this important for maintaining, strengthening or entering into relationships?

Doreen

Every Elder has a different protocol. In the beginning, I never accepted tobacco, but once I found out the true story behind the tobacco, I accept it all the time. I pray with it, and I take it to the cemetery. I take it back to the land. This is why every Elder should be consulted. [Ask] “what is your protocol” because it’s all so individual.

William

I agree with Doreen about tobacco. You have to ask first if they accept tobacco. The other thing is … if you invite an Elder … ask what the topic is. All the Elders are experts in different areas, for example, stories, hunting, trapping. So, ask Elders what their area of expertise is.

Always be careful of the protocol. Always ask, “what should I do?”

Mary

Learning how to do protocol is part of the learning process, and it’s a way to get to know the culture of all the different areas. It’s always good to ask about it. Don’t be shy, ask, “what is the protocol in this area?”

A while ago I had to do a presentation on the use of tobacco and it was elementary grades. After I finished, some of the kids wrote me a letter and one of the letters asked me … “I thought tobacco was a bad plant, that it’s not healthy.” I had to explain that the plant itself is not bad, it’s how people use it. It’s not unhealthy in itself … that all things on earth, all natural things, are supposed to be used for good, but sometimes people overuse them or don’t use them in a good way.

Those kinds of things I think people need to think about and, for people like myself, the cultural keepers, have to explain.

We all grow in our knowledge ourselves. We didn’t spring out of childhood just knowing everything, so over the years, I think we’ve learned all the ins and outs of protocol and we end up with practices that are true to ourselves and true to what we believe in.

Circling back to protocol, it’s very important — important as a culture and a cultural learning tool itself and for opening doors to all kinds of knowledge.

How can non-Indigenous teachers be effective allies?

Doreen

My whole thing is, get to know us. Get to know who we are. To be able to teach with respect to our children, I think it’s very important to get to know who we are and educate yourself on First Nations, Métis and Inuit, because we’re all different. I think that’s the biggest way that teachers can become allies and support our cultures—get to know us and be part of us. Get to know our ways of knowing, our ways of being so our students, our youth, can be proud of who they are, to continue along their path.

William

If somebody gives you a gift, never say no. Start building yourself [into] a pillar in the community by doing small things. Smile, respect, acknowledge. The other thing that teachers can do is learn the Cree language. For example, tansi — that means how are you?

Be positive. Always think positively when you see families, Elders, kids. Love their kids. Always be kind to them, the kids and everybody else. It makes

a difference.

Mary

Learn about us. Get to know us, but don’t take over. The best allies for me are people who get to know you and get to know about your culture.

Read more

View the entire digital issue of the ATA Magazine

See the latest issue