In May 2025, CBC journalist Amina Zafar reported that “Canada ranks 19th out of 36 countries in well-being of children and youth, behind other wealthy countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark and France, according to a new report from UNICEF [United Nations Children’s Fund].” (“Canada ranked 19th out of 36 countries in child well-being, UNICEF says.” CBC News, May 14, 2025.)

The news report raised questions about why Canada lags in child well-being when it consistently ranks highly on other global indices, such as U.S. News and World Report’s Best Countries.

The UNICEF report noted the current global context is reshaping childhood. In addition to "[the] 'three Cs' – COVID-19, conflict, and climate – childhoods are being transformed by the 'two Ds' – digital technology and demographic change" (UNICEF 2025, 1). The report emphasizes that wealthy countries, including Canada, must do more to create conditions that allow children to thrive as healthy, productive citizens.

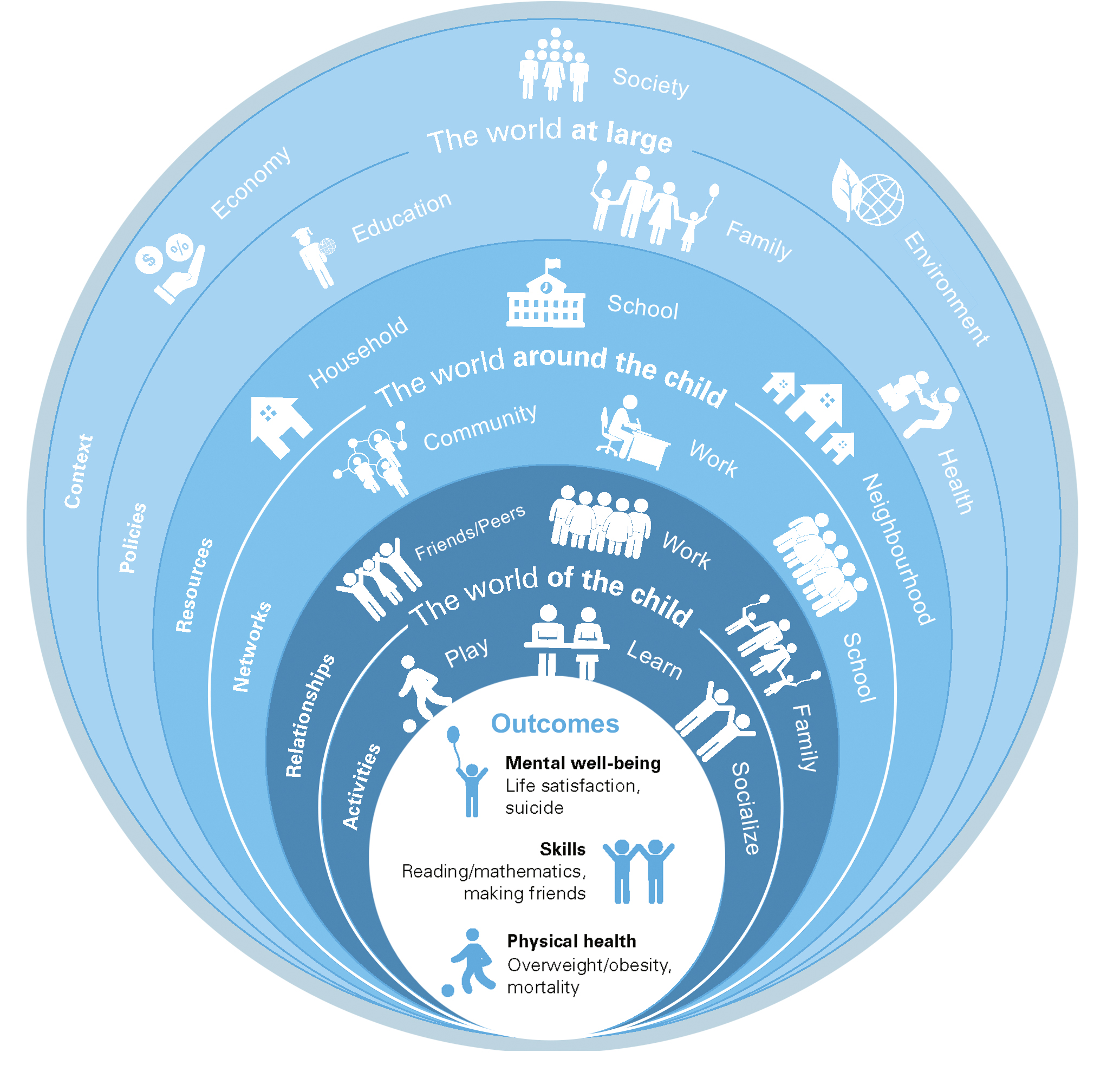

Titled Innocenti Report Card 19: Child Well-Being in an Unpredictable World, the report draws on health databases and international surveys such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Covering the years 2018 to 2022, it examines children’s well-being across three dimensions: mental well-being, physical health and skills. Of the 43 countries identified in the report (mostly members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the European Union), only 36 had complete data sets, which determined the final rankings. The report framed its findings through an ecological model of child well-being, underscoring the interconnected influences of family, community and broader societal factors.

Mental health

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is more than the absence of mental illness; it also includes "elements of happiness, life satisfaction and a sense of flourishing" (UNICEF 2025, 14). To capture this dimension, the report examined two main indicators of mental health: life satisfaction and adolescent suicide.

Acknowledging that the two indicators paint only a broad picture of children's mental health, the report noted that it has been in decline for some time. Suicide trends were mixed: 43 per cent of countries, including Canada, reported improvement; 40 per cent saw worsening rates; and the remainder were stable. Life satisfaction proved more telling, with "the large majority of countries” reporting a drop in satisfaction between 2018 and 2022 (UNICEF 2025, 17).

Factors associated with higher life satisfaction included regular physical activity, frequent conversations with parents or guardians and appropriate use of digital technology. In contrast, bullying, social isolation and limited parental contact correlated with lower satisfaction. Gender differences were notable: girls were less likely than boys to report high life satisfaction during the study period.

UNICEF recommended improving access to mental health services such as counselling and social–emotional learning, reducing the stigma associated with mental health, supporting families and expanding opportunities for meaningful activities that enhance children’s sense of belonging and well-being.

Physical health

Physical health was assessed using child mortality and obesity rates. Encouragingly, since 2020, child mortality in high-income countries has been halved, reaching just one death per 1,000 children. Most deaths now stem not from disease but from external causes such as accidents, violence or drowning.

However, new challenges threaten children’s physical health. Climate change, pollution and increasingly sedentary lifestyles are undermining gains from vaccines, medical advances and improved access to care. To address these issues, UNICEF called for structural reforms: affordable access to nutritious food, stricter pollution regulation, and national policies promoting healthy eating and physical activity.

Skills

The report evaluated skills using two indicators, academic skills and social skills. Academic performance was measured through PISA scores, which in 2022 showed “by far the biggest drop in test scores in the OECD-23 group of countries…a decrease of 15 points in mathematics and 10 points in reading” (UNICEF 2025, 45). Interestingly, Canada maintained its relative position in the PISA rankings, placing sixth out of 42 countries.

Potential explanations for the global decline included socioeconomic inequality, disruptions caused by COVID-19 and the widespread adoption of digital technologies. Students cited social and psychological barriers as their greatest obstacles during lockdowns: lack of motivation, difficulty understanding assignments and lack of access to learning support (UNICEF 2025, 48).

Social skills, closely tied to learning outcomes, revealed further disparities. Boys were more confident in making friends, while girls and children from higher socioeconomic backgrounds demonstrated stronger empathy and emotional competencies. UNICEF recommended adopting a skills framework that ensures all children acquire foundational literacy, numeracy and social–emotional competencies as the basis for lifelong learning and critical thinking.

Conclusion

The UNICEF report makes clear that while progress has been made in reducing child mortality in high-income countries, substantial challenges remain. Improving child well-being requires building communities where children feel they belong, equipping them to navigate a changing world and eliminating inequality. Achieving these goals demands sustained governmental commitment and financial investment. There is still much work to be done, and school systems and families have a large role to play.

References

UNICEF Innocenti—Global Office of Research and Foresight. 2025. Innocenti Report Card 19: Child Well-Being in an Unpredictable World. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti. www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/11111/file/UNICEF-Innocenti-Report-Card-19-Child-Wellbeing-Unpredictable-World-2025.pdf.

Zafar, Amina. “Canada ranked 19th out of 36 countries in child well-being, UNICEF says.” CBC News, May 14, 2025. https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/unicef-children-canada-1.7534521.