A leader builds positive working relationships with members of the school community and local community.”

— Alberta’s Leadership Quality Standard (LQS) for school leaders

The above expectation is set out by Alberta’s 2023 Leadership Quality Standard (LQS) for school leaders. According to the LQS, indicators of this competency include demonstrating commitment to the well-being of members of the school community; creating a warm, safe and caring environment for students and staff; and showing concern and empathy toward others. This human-centred and relational approach to leading a school community means that school leaders must provide emotional support in their interactions with colleagues, students and other members of the school community.

A May 2023 survey conducted in partnership with the Alberta Teachers’ Association found that Alberta school leaders are experiencing both satisfaction and fatigue with respect to the emotional support they provide, as well as a variety of burnout symptoms.

Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue

Compassion involves noticing the suffering of others, experiencing empathy for their suffering, then taking action to relieve the suffering. Providing this type of support during times of crisis or trauma can create compassion fatigue and compassion stress for the caregiver, potentially leading to symptoms that resemble post-traumatic stress disorder in its most severe form (ATA and Kendrick 2020). On the other end of the compassion continuum is compassion satisfaction, which helps protect mental and emotional well-being. Compassion satisfaction results when caregivers find ways to help others and know that their efforts make a difference for those they are helping (ATA and Kendrick 2020).

For this particular study, the levels of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in school leaders was assessed based on a validated scale called the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) Scale Version 5 (Stamm 2012).

Using this scale, data collected using an online survey was converted into a score that reflected levels of compassion fatigue and satisfaction being experienced by participants at the time they completed the survey. Across the 104 participants, the average score for compassion satisfaction was 32, indicating a moderate level, and the average score for compassion fatigue was 35, also indicating a moderate level.

These moderate levels for both compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction demonstrate the complex nature of these phenomena for school leaders. The two phenomena coexist in a school leader’s work life as these individuals can experience both the joy and the pain of caregiving in their regular work day.

However, when school leaders were asked, upon seeing their ProQOL scores, which concept related most strongly to their mental state, 67 per cent of them identified with compassion fatigue. When asked why they selected compassion fatigue, school leader participants shared many reasons for their choice, such as feeling burdened by taking on the worries of others and feeling depleted by their efforts.

Participants who identified their emotional state as being closer to compassion satisfaction shared that they worked in supportive environments where they felt they were able to make a difference and build strong relationships.

Overall, school leaders’ responses demonstrate that they work in environments where they are trying to create positive school environments, but their work is unrelenting, underresourced, emotionally draining and not well respected.

Research has revealed that “acting against one’s internal emotions has a significant association with anxiety, stress, and diminished psychological wellness.” (Jeung, Kim and Chang 2022, 190). Given the LQS requirements and the intensive emotional labour that leaders have invested in their relationships at school, it is important to understand how the emotional work of school leadership can impact mental and emotional well-being.

School leaders and burnout

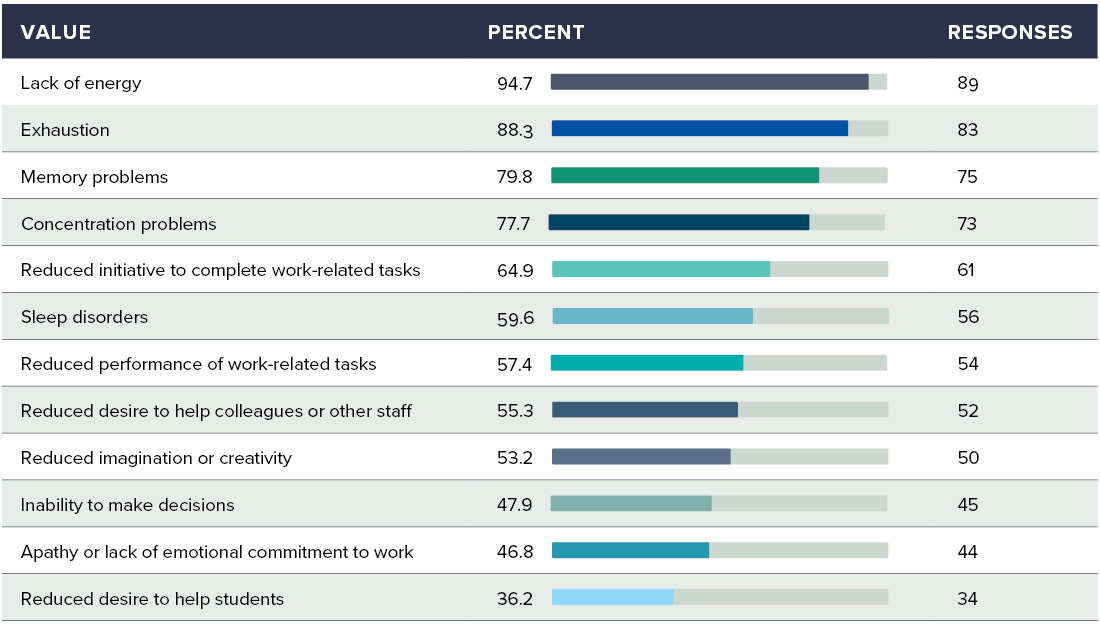

Responses from school leaders to the question, which of the following symptoms of burnout have you experienced since January 2023?

Burnout

Jeung, Kim and Chang (2022) define burnout as “a state of emotional, mental, and physical exhaustion caused by excessive and prolonged stress” (188). Burnout differs from compassion fatigue and compassion stress because, while both phenomena are linked to occupational hazards, compassion fatigue and compassion stress are linked to providing trauma and crisis care and can result from single occurrences, whereas burnout occurs over a longer period of time and results from many factors such as “work overload, multiple demands, emotional labour, and a lack of psychological safety” (Corrente, Ferguson and Borgeault 2022, 22).

To measure burnout, the May 2023 survey asked school leaders to review a list of 12 symptoms and check off those they had experienced within the previous four months. Lack of energy received the highest response rate, with 94.7 per cent of participants checking it off. This was followed by exhaustion (88.3 per cent), memory problems (79.8), concentration problems (77.7) and reduced initiative for work-related tasks (64.9).

This data suggests most of the school leaders participating in this survey were experiencing a variety of burnout symptoms. This finding is consistent with other research studies conducted by teacher organizations and academic researchers in both Canada and internationally (Agyapong, Obuobi-Donkor, Burback and Wei 2022; Corrente, Ferguson and Borgeault 2022; ATA and Kendrick 2020, 2021a, 2021b). The seriousness of the burnout symptoms experienced by school leaders invites a rethinking and change from “the dominant narrative [which] is that we need to monitor and improve the mental health and well-being of teachers because it might affect the mental health and well-being of students. Instead, the narrative needs to change to reflect the fact that teacher mental health is human mental health” (Corrente, Ferguson and Borgeault 2022, 33). This shift in narrative would delink school leaders from the important work they provide and would validate their right to be healthy as a part of our common humanity as opposed to only for the work they provide.

What now?

In this study, school administrators largely felt responsible for the school culture and strongly identified with the statements, "I am a caring person” (98 per cent) who finds it “difficult to separate my personal life from my life as an educator” (59 per cent) and feel “overwhelmed because my workload seems endless” (70 per cent).

This data illustrates the need to consider the occupational well-being of school leaders who work to build caring communities in schools for everyone. School leader participants identified a variety of activities they used to achieve wellness physically, mentally, emotionally, intellectually and spiritually. However, despite these self-directed and individual efforts, other measures must be considered. Developing safe and caring school cultures requires a collective approach, engaging with communities, students, teachers and school leaders through compassionate leadership.

For school leaders, these interventions should include increased system and organizational interventions from governments and school boards to ensure reduction in workload through the proper resourcing of mental and emotional health professionals to address the complex challenges in Alberta schools.

I Identify with compassion fatigue because …

“[I’m] having to take on the worries of my staff colleagues, students and their parents.”

“I feel drained most of the time. My efforts just don't seem to make a difference in the ways that I hope they would. There are so many children and families in crisis and not enough support.”

I identify with compassion satisfaction because …

“I enjoy seeing people prosper and gain positive self esteem as a result of my helping them.”

“I left a position where I had no autonomy and am now in a position to affect change.”

- Survey responses

This research report can be found on the Association’s website Research publications | Alberta Teachers' Association

Study methodology

This research project is intended to explore the emotional labour of education staff, including school leaders. Data was collected at three different time points: June 2020, January 2021 and May 2023. This article reflects a data subset from the May 2023 survey of participants who selected their role as school administration.

References

Alberta Education. 2018a. Leadership Quality Standard. Alberta Education. https://education.alberta.ca/media/3739621/standardsdoc-lqs-_fa-web-2018-01-17.pdf.

Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA), and A.H. Kendrick. 2020. Compassion Fatigue, Emotional Labour and Educator Burnout: Research Study. Phase One Report: Academic Literature Review and Survey One Data Analysis. Alberta Teachers’ Association.

COOR-101-30 Compassion Fatigue Study.pdf (teachers.ab.ca)

Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA), and A.H. Kendrick. 2021a. Compassion Fatigue, Emotional Labour and Educator Burnout: Research Study. Phase Two Report: Analysis of the Interview Data. Alberta Teachers’ Association.

COOR-101-30-2 Compassion Fatigue-P2- 2021 06 18-web.pdf (teachers.ab.ca)

Alberta Teachers’ Association (ATA), and A.H. Kendrick. 2021b. Compassion Fatigue, Emotional Labour and Educator Burnout: Executive Summary. Alberta Teachers’ Association.

coor-101-30-7_compassion_fatigue-executive_report.pdf (teachers.ab.ca)

Agyapong, B., G. Obuobi-Donkor, L. Burback and Y. Wei. 2022. “Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression among Teachers: A Scoping Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(17): 10706.

Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression among Teachers: A Scoping Review (mdpi.com)

Corrente, M., K. Ferguson and I.L. Borgeault. 2022. “Mental Health Experiences of Teachers: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Teaching and Learning 16(1): 22–43.

Mental Health Experiences of Teachers: A Scoping Review | Journal of Teaching and Learning (uwindsor.ca)

Jeung D.Y., C. Kim, S.J. Chang. 2018. “Emotional Labor and Burnout: A Review of the Literature.” Yonsei Medical Journal 59(2): 187–193.

:: YMJ :: Yonsei Medical Journal (eymj.org)

Maslach, C., and S.E. Jackson. 1981. “The Measurement of Experienced Burnout.” Journal of Occupational Behavior 2(2): 99–113.

Stamm B.H. 2012. Professional Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Version 5 (ProQOL). Idaho State University. ProQOL Manual | ProQOL.