Dr. Ellen Field is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Education at Lakehead University-Orillia, where she teaches climate change education and environmental education. Her research focuses on the policy and practice of climate change education. She is widely regarded as Canada’s foremost expert in climate change education in the K–12 sector.

The ATA Magazine sat down with Dr. Field to discuss her research and her message for teachers and system leaders.

(Responses have been edited for length and clarity.)

Q. What role can schools and teachers play in addressing such a complex, global issue like climate change?

A. The data has been clear on climate change for over 50 years. Have our systems changed accordingly? No. So we need to actually learn our way through it, and I think one of the ways that we can learn differently is by learning in schools that it’s okay to change our position based on the information we’re learning. So the classroom can be this very powerful intervention to build some of the capacities that we know the world needs more than ever.

At the same time, young people are already hearing about climate change in the news and increasingly experiencing its effects in their daily lives. When schools fail to address climate change in substantive ways, it creates cognitive dissonance, sending the message that what students are living through doesn’t matter in their formal education. For schools to be responsive, they need to respond to climate change across multiple dimensions: integrating it into curriculum, updating school policies and practices, preparing for climate-related emergencies, and helping students understand both the urgency of the crisis and the pathways to action. This includes building skills for participating in low-carbon economies and building resilient communities.

Q. Here in Alberta, many teachers are in a situation where the students come from households that rely on fossil fuels for their livelihood. How can they address climate change in that type of setting?

A. I think approaching it as an inquiry project and really focusing on an openness to learning. There needs to be an agreement among students that the learning is not going to fall into personal attacks, and that opinions can be expressed, and the learning space is a place to really investigate and learn more about these topics that are very political and very controversial at times.

You don’t want to necessarily be positioning that this is the absolute way to see an issue. You can talk about the consensus of the science, but when it comes to implementation of policy and projects, these are challenging things and you do have to weigh environmental, social and economic impacts.

These are complex topics, so they need complex pedagogy and processes for students to be able to learn that complexity. As soon as we start to flatten it and say, well, we all have to be antipipeline or we all have to be propipeline, that’s problematic. So we need to cultivate that willingness to learn and also to learn from each other and to do more research and have flexibility in our position based on what we’re learning.

Q. Teachers in the K–12 system are required to teach the curriculum that’s created by government. Given this constraint, what is your message to teachers who are concerned about climate change?

A. Our curriculum is still quite dated, and I think we need to find whatever windows we can as teachers to be responsive to all of the ways that life in the 21st century is changing. It’s often through motivated teachers that this happens, and then policy slowly shifts over time. But teachers don’t need to wait. They can integrate content and update their practices much faster, and our research shows that motivated teachers do and are teaching climate in subjects where there may not be direct curriculum links. Math, health and art are subjects where we find teachers bringing in climate content.

Teachers also have tons of experience in terms of how to scaffold a lesson that’s appropriate for the students in their room based on the subject they’re teaching. I think we sometimes forget that teachers are very good at planning, very good at thinking about who the students in the room are and what their needs are, so often they just need a little bit of support or professional development to integrate it. Probably after six hours of support, you could have a lot of teachers feeling a lot more confident.

Q. Where can teachers turn for this type of support if it’s not available through their employer?

A. There are many climate change teaching resources available. Our research has shown that when it comes to teaching climate change, most teachers create their own lesson plans or pick aspects from already developed resources from environmental nonprofits.

I think it is important to think about their subject, their students and their local experiences of climate change, and then look for climate activities that will align.

Learning dimensions of climate change education

Cross-disciplinary research suggests climate change education should focus on the following learning dimensions.

Cognitive

- Teach the scientific consensus on climate change.

- Foster critical-thinking skills and media literacy.

Socio-emotional

- Incorporate socio-emotional considerations to overcome feelings of ecoanxiety, denial and inaction.

Action-oriented

- Use teaching methods that are participatory and place-based.

- Focus on collective action.

Justice-focused

- Link and strategize with other justice-related issues.

- Address who benefits and who is most affected by our collective inaction.

| Scientific consensus |

|---|

Source: UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). |

How comfortable are you engaging in classroom discussions about climate change?

I’m fairly comfortable myself, but I take it from an angle of let’s be critical thinkers, and I change it more into a lesson of how do we establish what is information, what is misinformation?

In my small, rural community, I can’t pick a side because there’s going to be people on both sides, so my whole thing is, if I can teach my students to be critical thinkers and go seek the information, then I’m not painting them with my liberal ideas.

These kids are constantly worried about those kinds of big ideas, and it wraps around into so many other topics.

Stephanie Cumbleton, president Aspen View Local No. 7

Junior/senior high mathematics

Boyle School, Boyle

I’m pretty comfortable doing it because science is a thing. Like, the facts are kind of undeniable. I know there’s lots of people who are climate change deniers, but I feel like [if] we present everything in a cohesive way and are able to have these conversations, then that’s fine.

Shannon O’Halloran

English and social studies

Westwood Community High School, Fort McMurray

I’m fairly comfortable, but I probably have a different set of opinions because we’re farmer- and oilfield-based communities and so my version of climate change is maybe a little bit different than somebody from the city, but I feel like I’m fairly comfortable talking about it from a farming and oilfield perspective.

Megan Wianko

Grade 5-6

Gus Wetter School, Castor

Very comfortable, because back when I was in university, like in 1983 when I graduated, we were talking about it then, so I was fairly comfortable talking about it in front of the class.

Blaine Woodall

Math-science teacher

Calling Lake School, Calling Lake

Confidence factor

32% of Alberta teachers feel they have the knowledge and skills to teach about climate change.

Source: Canada, Climate Change and Education: Opportunities for Public and Formal Education, Dr. Ellen Field, Lakehead University.

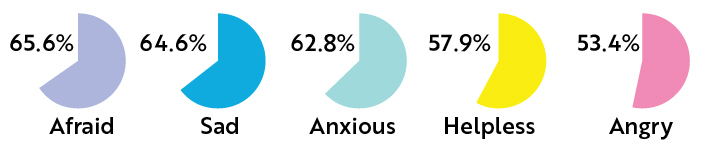

Canadian students are feeling climate anxiety ...

Climate change makes me feel

... but also hope.

Can something be done about the climate crisis if people work together?

Source: Importance of Climate Leadership in Schools: Pedagogy & New Opportunities for Learning, Dr. Ellen Field, Faculty of Education, Lakehead University.

How can teachers model ecoresponsibility?

1. Make sustainable transportation choices.

Walk, bike, take transit or carpool to work when possible and highlight active transportation benefits in class discussions. Organize a walk- or bike-to-school challenge to model sustainable commuting.

2. Teach and practice energy conservation.

Involve students in classroom energy audits and identify ways to reduce energy waste, like turning off lights, projectors and electronics when not in use and opening blinds for natural light instead of using overhead lights.

3. Incorporate outdoor and experiential learning.

Take lessons outside when possible to foster a connection with nature by using nearby green spaces, school gardens or local parks to enhance learning

ATA Global, Environmental and Outdoor Education Council.

Environmental education and sustainability programs in Alberta schools

Alberta Council for Environmental Education

- Offers programs such as Alberta Youth Leaders for Environmental Education.

- Supports integrating environmental education into the K–12 curriculum.

- Operates the Alberta Green Schools Initiative, which supports students’ environmental, energy and climate change education.

Alberta Environment and Protected Areas

- Provides various environmental resources and information to schools and youth groups, facilitating access to a variety of educational materials and programs.

Alberta Parks

- Education programs provide educational resources and programs, including teacher workshops and in-class presentations such as "Kananaskis in the Classroom," which brings environmental education directly to students.

Calgary Board of Education (CBE)

- The CBE Sustainability Framework 2030 guides environmental education and initiatives, emphasizing energy management, waste reduction and sustainable operations.

EcoSchools Canada in Alberta

- Provides a certification framework for K–12 schools to achieve bronze, silver, gold or platinum certification by engaging in sustainability and climate action projects.

Edmonton Public Schools

- The division has set carbon reduction targets and are exploring renewable energy options, waste reduction strategies and sustainability education.

Government of Alberta

- Environmental educator workshops provide training on nature and water resources, equipping teachers with tools to incorporate environmental education into their practices.

Inside Education

- Offers classroom programs, field trips and teacher professional development focused on Alberta's natural resources and environmental topics. Their programs encourage critical thinking and provide hands-on learning experiences related to energy, forests and water conservation.

Green initiatives

École McTavish Public High School

This Fort McMurray school has invested more than $750,000 in solar panels and features both indoor and outdoor gardens.

Christ the Redeemer Catholic Separate Regional Division No. 3

This division has been recognized for constructing “green” school facilities. Notably, Holy Trinity Academy in Okotoks was built to LEED Gold standards, making it the first high school in Canada to receive this prestigious recognition.

Information compiled by the ATA’s Global Education Global, Environmental & Outdoor Education Council (GEOEC).

| Embrace evidence-based education and action |

|---|

Source: Polluting the Schools: The Influence of Fossil Fuels on K–12 Education in Canada. A report by the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment and For Our Kids, February 2025. |

Countering misinformation

| Climate change myth or misconception | More accurate climate/environmental information |

|---|---|

| “The climate has changed before. It has nothing to do with humans.” | Many factors can change the climate. Right now human activities, especially burning fossil fuels and the destruction of ecosystem resilience, are the major factors. |

| “Scientists are still debating climate change.” | Ninety-seven per cent of scientists agree that climate change is happening and is human-driven, and over 99.9 per cent of studies confirm those positions. |

| “There have always been natural disasters. What we’re seeing now is no different.” | Climate change is increasing the overall frequency, erratic occurrences and intensity of dangerous weather events like storms, droughts and high temperatures. |

| “There’s nothing we can do about climate change.” | Because humans are driving climate change, humans can slow it down by doing fewer of the things that cause it and finding different ways to get what we need and want. |

Recommended resources

Accelerate Climate Change Education in Canadian Teacher Education

This project supports climate change education (CCE) in preservice and inservice teacher education across Canada through consultations, webinars, online courses, grants and resources.

Columbia Basin Environmental Education Network (CBEEN)

The CBEEN website has a list of recommended resources to help teachers deliver accurate, effective, empowering and age-appropriate climate change lessons and programs.

International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report

Working Group III: Mitigation of Climate Change

This report provides an updated global assessment of climate change mitigation progress and pledges, and examines the sources of global emissions.